Jonah Naplan January 23, 2026

One hour and forty minutes of Chris Pratt trying to solve a mystery across a variety of screens might initially sound like fun to fans of the actor. But as “Mercy,” the newest film from Timur Bekmambetov, unfolds, it becomes tantalizingly clear that it’s not committed to the entertainment the trailer seemed to promote. This visionary concept had some potential: it’s 2029, and the city of Los Angeles has dramatically evolved to rely on artificial intelligence as a figure of the national justice system that the convicted must appeal to or else face execution. Where it ultimately ends up, however, feels like a betrayal, an inauthentic twist of fate that offsets the focus, and just as well could have been generated by AI, itself.

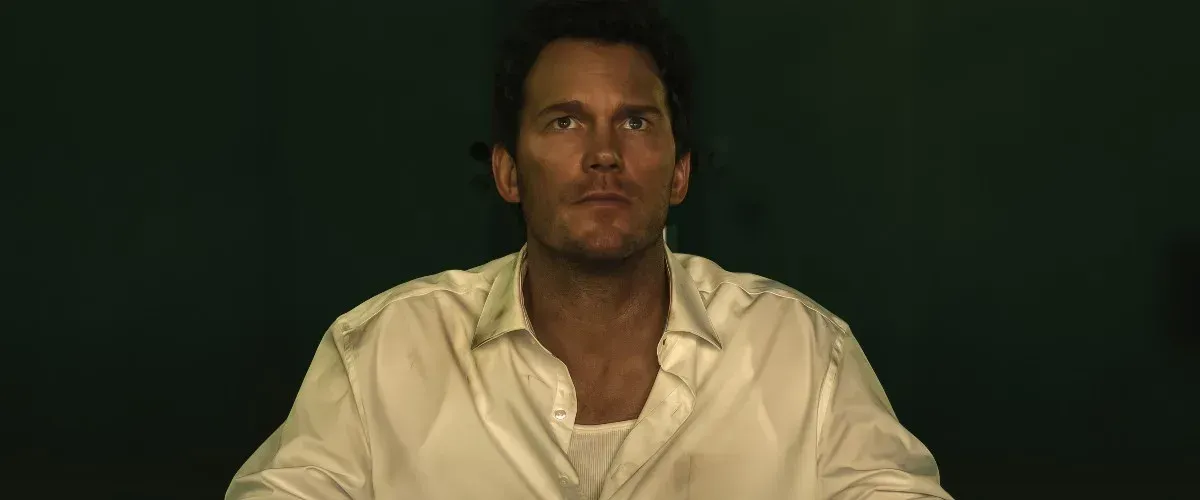

Pratt plays Chris Raven, an LAPD officer who’s put on trial for accusations of killing his wife Nicole (Annabelle Wallis). Strapped to a chair in a nondescript room, he has 90 minutes on the clock to prove his innocence to the AI Judge Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson) before execution. A founding backer of this innovative “Mercy” program itself, and having sent it some of the program’s first criminals, the irony of him now being the subject of the judge himself lingers all throughout the movie’s surprisingly solid first act. The parameters are fairly straightforward: if he can’t lower his statistical “guilt level” below the 92% threshold before the clock winds down, with all the technological resources—the entire LA surveillance camera system, private identification files, the entire web “cloud,” etc—he might require at his disposal, it’s lights out for him. As doors start opening, and the investigation begins to unfold, however, “Mercy” loses its rhythm and ultimately abandons the gripping promise of those opening scenes.

Written by Marco van Belle, “Mercy” progressively has the nerve of something released straight to streaming, and not in the good, turn-your-brain off way, but in the cheap, sketchy sort of way like in the recent “War of the Worlds” and “The Electric State.” Stranger, though, is the film’s marketing campaign, which fiercely promotes experiencing it in IMAX 3D. But there’s nothing about “Mercy” worth paying extra money to see, and its best scenes would probably best be viewed at home anyway, if somehow you’re still interested. I didn’t personally see the movie in that extravagant format but I can’t imagine it would add a whole lot to watching one guy sit in a chair and talk to a computer.

The versatile “screenlife” format has been used excellently before in films such as Aneesh Chaganty’s “Searching” and its follow-up “Missing,” but there’s not a single stand-out moment in “Mercy” that uses the platform anywhere near as creatively as those movies. What has the potential to disclose the inner lives of characters, convey a big plot reveal, or act as a familiar throughline for all the investigative mumbo-jumbo is ultimately wasted on a collection of cut-aways that struggle to build on each other or create a linear relationship. The editing by Austin Keeling, Lam T. Nguyen, and Dody Dorn works really hard to convince us there’s a lot going on, intercutting Ring doorbell, drone, and FaceTime footage in between shots of Pratt’s panicked eyes and Ferguson’s clenched, emotionless visage to create “action.” But it’s not effective because the rhythm isn’t there.

It’s funny how two actors typically known for their roles in big action franchises have each been rendered immobile in their respective parts here. Pratt has of course headlined both the “Guardians of the Galaxy” and “Jurassic World” movies, while people often overlook the virtuoso work of Ferguson in the “Mission: Impossible” series. Yet never have I been so underwhelmed by either of them. As we watch Pratt confined to a chair and Ferguson trapped in a network of zeros and ones, we, too, feel imprisoned in our seats. The feeling of being held captive is heightened by the plotting, which builds up the idea of the ticking clock, quite literally pacing most of the movie around its countdown, and then shifts to a new focus entirely in the last 25 minutes, once the “reckoning,” so to speak, gets easily resolved. It ends on a note that might be hard to read for some viewers because it’s so choppy and misguided, but it seems to endorse AI, which is unmistakably an unsavory touch for a big budget studio movie featuring major stars in 2026.

Nothing about “Mercy” offers mercy to the viewer. If they aren’t bored by the milquetoast plotting then they’ll be off-put by the messaging. It’ll be tossed onto streaming before you know it, and if its willpower becomes too oppressive, you can just turn it off and go do something else.

Now playing in theaters.